Crumbs at the Slophouse

There was a man at the ice creamery the other day and I cannot stop thinking about him.

He looked about 50. No family in tow, indeed no other travelling friends or acquaintances in sight. From his person there were wires, running out of his ears and a battery pack to a pole which he held in outstretched arms. At the end of the pole was a phone and with it he was broadcasting live to a streaming service where people were, apparently, tuned in to listen to him scream ice cream flavours with precisely zero accompanying context.

'Dubai chocolate!' he yelled. 'Noisette!' The way he shouted vanilla, like he was the first person in the whole world to extract it from the bean, was especially confronting. He yelled out every flavour in the store and then left.

This is what it is like to have literally anyone in the entire world try and talk to you about 'artificial intelligence' but especially if you are, say, Atlassian co-founder and chair of the Australian Tech Council Scott Farquhar. He told ABC's 7.30 program on Tuesday, August 12:

All AI usage of mining or searching or going across [copyright] data is probably illegal under Australian law and I think that hurts a lot of investment of these companies in Australia.

Farquhar was responding to one of the bi-decadal frag grenades thrown by the Productivity Commission at the creative arts in Australia; a sector, almost by definition, that it can never hope to understand. When the Productivity Commission rolls the all-terrain tracks of its extraction machinery into town it is a fairly safe bet that it does so with all the grace of an economist invited to give the eulogy for an industry he has long wished dead.

If you think that is an overwrought metaphor, allow me to show you precisely what it is the Productivity Commission is countenancing in its recently released interim report Harnessing Data and Digital Technology:

There are concerns that the Australian copyright regime is not keeping pace with the rise of AI technology – whether because it does not adequately facilitate the use of copyrighted works or because AI developers can too easily sidestep existing licensing and enforcement mechanisms. There are several policy options, including:

• no policy change – that is, copyright owners would continue to enforce their rights under the existing copyright framework, including through the court system

• policy measures to better facilitate the licensing of copyrighted materials, such as through collecting societies

• amending the Copyright Act to include a fair dealing exception that would cover text and data mining.

We are talking about mining of work created by actual human beings for the training of large language models (LLMs) that are not exactly AI – certainly they are not intelligent, even approximately so – but which have been included in the catch-all term because an industry built on smoke and mirrors doesn't mind committing more than one category error in its marketing confusopoly.

Here we have an entire magician's alliance shouting 'vanilla' at the ice creamery as if they invented the fucking thing, as if they alone have brought the wonders of this exotic flavour to your lips.

They just read some text!

It is an irony not lost on me that the start of this very same Prod Comm report begins with the assertion of various copyright clauses, including copyright owned by third parties which, it says quite correctly, must be respected. And then.

And then!

Then we are introduced to the vague 'concerns' that Australia's copyright regime is 'not keeping pace with the rise of AI technology' in part because it does not 'adequately facilitate the use of copyrighted works'.

In the interests of linguistic efficiency, for I know the productivity tsars would not wish to hesitate in getting to the point, we are talking about theft. One of the proposed solutions to the fact that these AI companies are already stealing the work of creatives, writers and artists is not to wonder – not even performatively – about how to protect the output of the creators but to suggest formalising the theft.

At least when the corporations steal our coal they have to dig it up first.

Some of my best friends are economists. I am not ignorant of the actual argument being made. It is no doubt correct if, among your priors, you believe that hyper-industrial scale theft of the the sum total of human creative output would be easier for data mining companies if we just let them do it. That's axiomatic! Of course it would be. And it would be easier – read, more profitable – for the rapacious prospectors of the Pilbara et al if the iron ore just climbed out of the ground from the sheer magnetic desire of the people who willed it.

But I suppose it wouldn't really be called mining, then, would it. Just, I don't know, sort of using an MRI machine to steal jewellery from people and then calling Harvard to boast about it?

If your incredible business idea – key word here, business – is to bake cakes for sale and then you complain that you have to pay for eggs and flour then I have some terrible news about your business idea and also quite possibly your soul and brain. All I can hear is the old broad spectrum admonishment of parents everywhere when the elements of this problem arise: When I was young and we couldn't afford to do something we just didn't do it.

To be fair to the productivity boffins, they don't care to deal with the output of AI and/or large language models and whether the 'work' fever-dreamed up by those models infringes on our copyright. The PC says it is only concerned with the part that might most affect productivity by 'stifling' innovation: the training of those models. That's the bit where OpenAI, Meta and whatever the fuck Grok is just get to hoover up our work for the sake of training the hallucinatoriums beloved by fascists everywhere.

Let me be as real as I know how. Even if the the universe arranged itself in just such a way as to devise a scheme in which our creative work could be bought and could be paid for, even at an above-market price – say, for instance, something very similar to the existing copyright law save for the price and lack of enforcement – for the use of training AI models I would not give it to them. There are many great uses for types of artificial intelligence – in medical research, hurrah! – and I am sure there are one or two use cases for a large language model that are helpful to more than the person using it to write their emails or astro-turf an election. But I do not want them. I have a negative want for them. I yearn for their destruction.

Sam Altman, who might have sold tulips in another age, heads OpenAI. This company is allegedly worth $500 billion (0r a cool $766m in dollarydoos) but, by his own estimation, this is largely because AI is in a bubble phase with a kernel of a useful technology around which 'overexcitement' has grown. That's right. The cake stall that can't afford flour or eggs is worth one-eighth of Microsoft or Apple.

Altman seems to hallucinate almost as much as his baby Chat-GPT and they also share a similar lack of humanity. The chatbot (Altman, not ChatGPT) told journalists at a dinner this week that we should expect to see OpenAI spend 'trillions' of dollars on life draining data centres in the 'not too distant future'. Firstly, sure, whatever, you might or might not. Right now your company can't make a profit. And I truly hope it never does. That hasn't stopped investors from handing over cash in the frenzy of speculation so maybe you will manage to stump up the money. Maybe you will build those toxic – emotionally, spiritually, environmentally – simulacra engines and suck up all the water and tank the energy grid with the demand for the worst art ever made.

Executives have been setting fire to other peoples' money for decades now but I don't see why we should be drafted to help them in the cause. Or at least, not in the way the Productivity Commission expects us to.

The Productivity Commission likes to talk about innovation but this is not that.

Enron did it first.

And before them, any kingdom that went to war so often the people could no longer afford to eat.

But if it's setting fire to money they want help with, I know a few creatives that could help. About 7 million in one class action alone, if it gets the go ahead after truly staggering appeals from AI company Anthropic which stole their work and is now arguing before the court that if they have to pay for it, or settle enormous fines, they'll be bankrupted.

'One district court's errors should not be allowed to decide the fate of a transformational GenAI company like Anthropic or so heavily influence the future of the GenAI industry generally,' the company's attorneys wrote in an appeal filing to the United States 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Allowing the biggest ever copyright class action to go ahead, they argue, would be a 'death knell' with 'potentially ruinous liability' attached to Anthropic and a similar effect across generative AI models owned by other evangelists like Altman who didn't like it when he accused the Chinese of stealing his model of other stolen things.

Bankrupting the entire industry?

OK fine, I'll help.

In fact, I volunteer.

Addenda

Tinker Tailor Scolded Why

I bought a pair of pants through a fairly comical exchange of badly spoken French and badly spoken English and the pair I tried on fit very nearly almost perfectly save for a tightness around the waist. In bad French, I asked for the next size up but the vendeuse told me either that they didn't have it or that she would not go and get it. Both options seem live at this point. To be fair to her, she seemed to indicate that the pants fit well everywhere else so I would be better off taking them to a tailor and having the waist taken out – the most complicated sentence in our exchange which we achieved through the linguistic equivalent of approaching a potentially dangerous wild animal in the woods.

In a past life I would have baulked at the pant-based admin required and given up on the whole project. Alas, I wanted them. I bought the pants and then took them to a local tailor, a jolly and efficient woman who spoke no English at all, as is her right. Her daughter and/or friend on the phone translated for us and all was well with the world. I returned in the afternoon to pick them up and, in French which I actually understood, the tailor said: 'I've taken them out 5cm for you. If they don't fit you'll just have to lose weight.'

Her daughter slash friend was in the room at this point and before she could translate for me I looked at her and we both started laughing.

My New Personal Assistant

A card arrived in the mailbox the other day from a Mr Sidiki, offering a compelling range of services that I didn't even know I needed. He's a sort of handyman, I gather, although his gifts are many and best categorised under 'seer'. Translating, he offers:

'Thanks to his powers, he will help you solve your problems: Love, disenchantment, protection against dangers and enemies, work, licenses, sexual impotence, luck at games, bad luck at school, marital crisis, quick return of your loved one, if he/she has left you, he/she will return like a dog behind his/her master and become inseparable again.'

Alright, monsieur. I'm listening.

What I enjoy most about this is the alacrity with which Sidiki dips into, and moves beyond, the anodyne. See, you can have your enemies vanquished, your disenchantment vapourised but also, real quick, if you're having trouble getting a forklift ticket or similar than Mr Sidiki is also a Registered Training Organisation and can help you get a licence or three. Would that be of interest? No, well, moving right along: sexual impotence. They don't do that at TAFE. This is what we call market differentiation, Sidiki.

I enjoyed all of this, but Sidiki turns poetic when he begins the sell on his ability to return your loved ones, guaranteeing not only to have them come back to you but to do so as a dog might, tail between its legs, admonished by its master (my god).

In the very next line, however, we are treated to the real-time thought process of the writer who, having promised the return of lost loves like dogs, turns his mind to whether he might be able to extend his powers to the return of pets. You'll not be surprised to learn that this is also within his ken.

'Disappearance of your cat or dog, all problems have solutions.' That could read as a promise to find a lost pet or, given where we've come from, as a threat to disappear them. His business hours are 8am to 8pm.

Some Personal Updates and What Have You

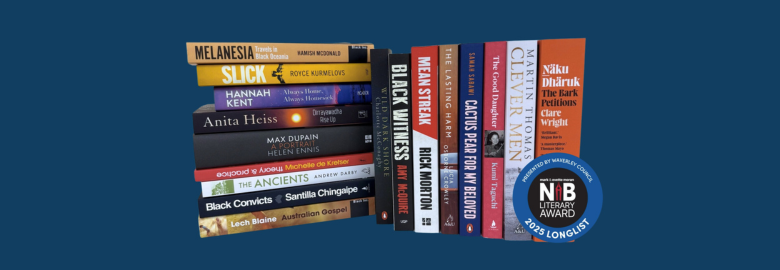

This seems somewhat unedifying, but over the past few weeks I've been treated to some lovely and unexpected news about my book Mean Streak which you are all no doubt very much sick and tired of hearing about.

But, well, it is not over yet.

Mean Streak has been longlisted for the Mark and Evette Moran Nib Literary Award, a national prize hosted by Waverley City Council which recognises works that 'best fulfill the criteria of literary merit, quality research, readability and value to the community'.

I know so many of the writers on this longlist – indeed read and chose some of them with other judges for other prizes – and to be featured alongside their work is a reward all its own.

A few days after this news, my publisher Catherine Milne (who has put up with me a lot throughout the making of this book) emailed to tell me Mean Streak had been shortlisted in the non-fiction category for the Prime Minister's Literary Awards 2025 and I almost had a little fit. The biggest lit prize in the country and my awful baby is on it. I say awful because I both hate it and am proud of it, never clearly one or the other. So to read the judges' comments, below, was especially clarifying.

I am glad and reassured. For a few days anyhow!

Rick Morton’s Mean Streak is a painstaking account of the development of Robodebt, a federal government scheme to illegally pursue welfare recipients for fake debts. It is an excellent example of the fusion of thorough journalistic methods with an empathetic understanding of the humans at the heart of the story. We understand the real debt suffered by people in trauma and financial crises, sometimes paid with lives. Morton’s writing redefines people demonised as ‘welfare cheats’ to victims of their own government. Morton combed the ample public evidence to develop a narrative to help the reader understand how modern government overreach occurs. He pays attention to the obfuscatory role of language, and how the presence and absence of words have implications beyond paper and screens. Morton is at his best when contrasting administrative amnesia with brief but devastating accounts of suicide and despair. His writing is distinguished by its engrossing storytelling, distilling complex policy and its aftermath and centring the experiences of vulnerable people caught in a Gogolian process. Though Robodebt began in 2014, a decade later it has incredible resonances with today’s global political situation, including political vendettas against individuals and demographics and the decline of frank and fearless advice in the public service. With single-minded determination, Morton successfully distils a government’s disgrace into an enthralling account of what happens when we lose our collective conscience.

Bendigo Write-Off Festival

To less fun writing news, I've been following the absolute clusterfuck of organisational and ideological bullying that is the Bendigo Writers' Festival / La Trobe University 'code of conduct' fiasco. I won't recap it here except to say as someone who has been to probably 100 writers' festival sessions now all across Australia since 2018 I've never seen anything like it. It makes me furious and sad. I am furiously sad. Had I been in Australia, I would have joined the dozens of writers who pulled out in protest and forced the collapse of most of the programming. A debacle that hurts writers, sure, but also the many people especially in regional Australia who want to attend these festivals precisely because they introduce us to ideas and ways of thinking about the world.

Now, of course, we know the 'code' was an eleventh hour retcon to respond to the Pro-Israel lobbying of an 'alliance' of academics who specifically targeted a Palestinian writer and advocate in the programming, Dr Randa Abdel-Fattah.

Shivers looking for a spine to crawl up. This alliance won't care that they've torpedoed an entire writers' festival. No damage is too great – as we have seen all too clearly in the unfolding genocide in Gaza and other war crimes there – to assure the Israeli government's most enthusiastic defenders of what the writer Ursula K. Le Guin once called 'unassailable safety' in her Earthsea series.

'Nature is not unnatural. This is not a righting of the Balance, but an upsetting of it. There is only one creature who can do that.'

'A man?' Arren said, tentative.

'We men.'

'How?'

'By an unmeasured desire for life.'

'For life? But it isn’t wrong to want to live?'

'No. But when we crave power over life—endless wealth, unassailable safety, immortality—then desire becomes greed. And if knowledge allies itself to that greed, then comes evil. Then the balance of the world is swayed, and ruin weighs heavy in the scale.'

Pin the Fail on the Pétanque-y

The Paris Pétanque Club, set up by three of my friends in Paris and moi, met on Saturday 9 August for its inaugural showing in a gravel bowling alley (that I have only just now learned is called a boulodrome, possibly the best thing I've heard in a while) just south of the Oberkampf district.

We played more games than I can count, drank more bottles of rosé than I care to count and stayed up and into the wee hours of the next morning through a series of events that have caused me unspeakable psychic harm, namely via the near complete and hopefully temporary regression to my 19-year-old self.

I cannot yet bear to trouble the now idle thoughts that plagued me for a full week afterwards in order to properly recount the finer details of what unfolded after the game itself ended.

All I know is that I heard the clacking of those boules in my nightmares, like a metronome, as my mind desperately tried to recover what had been blasted out of orbit by the wine.